Bitcoin blockchain: performance and scalability

Bitcoin is a decentralized electronic cash system that makes peer-to-peer payment possible without going through an intermediary. The original Bitcoin software was developed by Satoshi Nakamoto and released under the MIT License in 2009, following the Bitcoin white paper, Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System.

Bitcoin is the first successful implementation of a distributed cryptocurrency. Sixteen years after Bitcoin was born, there are about 20 million Bitcoins in circulation, and it has now reached a market cap of over $2 trillion.

Within the Bitcoin blockchain, a transaction means that a collection of inputs and outputs transfer the ownership of bitcoins between payer and payee. Inputs instruct the network which coin or coins the payment will draw from. Those coins in the input have to be unspent, which means they haven’t been used to pay someone else. Meanwhile, outputs provide the spendable amounts of bitcoins that the payer agrees to pay to the payees. Once the transaction is made, the outputs become the unspent amounts to the payee, and they remain unspent until the current payee pays someone else with the coin.

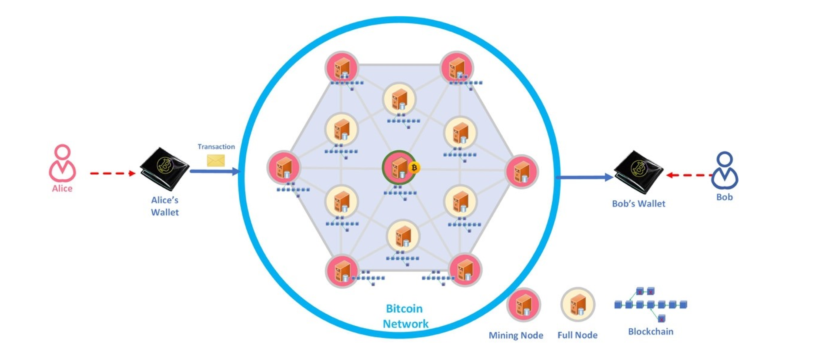

When, for example, Alice needs to pay Bob 10 BTC, Alice opens her Bitcoin wallet, and scans or copies Bob’s transaction address and creates a transaction with a 10 BTC payment to Bob. Once the transaction is digitally signed and submitted, it’s sent to the Bitcoin blockchain network.

After the transaction is broadcasted to the Bitcoin network, the bookkeeper node, usually a full node in a P2P network that receives the transactions, validates it according to Bitcoin protocol rules. If the transaction is valid, the bookkeeper adds it to the transaction pool and relays the transaction to the peers in the network.

Within the Bitcoin network, every 10 minutes, a subset of network nodes, called “mining nodes” or miners, collects all valid transactions from the transaction pool and creates the candidate blocks. They also create a coinbase transaction for themselves in order to receive rewards and collect transaction fees. In the event they “win the mining race” and add the block to the chain, all nodes will verify the new block and add it to their own copy of the blockchain. Magically, Bob will be able to see the payment from Alice — and 10 BTC in his wallet.

One of the major concerns in the Bitcoin network, or in general for any proof of work (PoW)–based blockchain, is that of scalability. By design, every transaction has to be verified by all nodes. It takes an average of 10 minutes to create a new block, with the block size limited to 1 MB. Block size and frequency limitations further constrain the network’s throughput. As a result, a Bitcoin block is able to accommodate an average of 2,700 transactions. With today’s payment systems, VISA is able to handle on average around 2,000 transactions per second (TPS), and the daily peak rate is around 4,000 TPS. As of 2025, Paypal can handle an average of around 193 TPS, or almost 17 million transactions per day.

Clearly, achieving Visa-like capacity on the Bitcoin network isn’t feasible. Higher performance and better scalability would require increasing the network’s transaction processing limit and conducting software enhancements for the Bitcoin network.

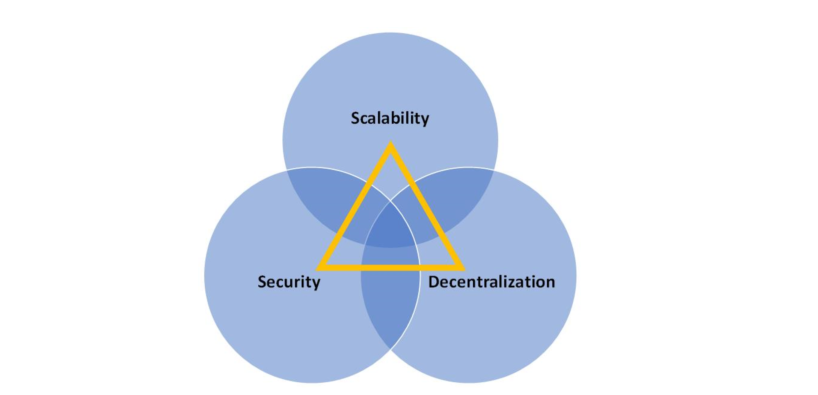

The blockchain trilemma addresses the “trifecta” of attaining scalability, decentralization and security on a blockchain network without compromising on any of them. Central to the trilemma’s premise is the assertion that it’s almost impossible to achieve all three properties within a blockchain’s system.

The following diagram is an illustration of the blockchain scalability trilemma.

Key to the concept of scalability is finding a way to achieve all three requirements at the base layer. The design choices of Bitcoin favor decentralization and security while making a sacrifice in scalability.

Bitcoin scaling solutions

There are many Bitcoin scalability solution proposals, which can be further divided into on-chain and off-chain scaling.

On-chain scaling

On-chain solutions, sometimes also called Layer 1 solutions, address scalability and performance issues in the Bitcoin blockchain network’s base layer. In terms of network latency, on-chain scaling provides the capacity to handle more transactions in the blockchain. Examples include SegWit, which fits a greater number of transactions into a 1 MB block, and Bitcoin Cash (BCH, symbol Ƀ), which simply raises the block size.

SegWit

SegWit (Bitcoin Improvement Proposal number BIP14) is short for “segregated witness,” which means separating the digital signature for a transaction. It was first introduced by Developer Pieter Wiulle at the Scaling Bitcoin conference in December 2015. The purpose of SegWit was to prevent non-intentional Bitcoin transaction malleability and allow optional data transmission, and to bypass certain protocol restrictions.

A Bitcoin transaction consists of three things:

a transaction input, which is the Bitcoin sender’s address

a transaction output, which is the receiving Bitcoin address

the amount of Bitcoin being sent, along with a digital signature that verifies the sender is eligible to send the coins

The transaction identifier changes if the digital signature changes. It turns out that Bitcoin’s code allows digital signatures to be altered when a transaction has still to be confirmed. Once a transaction is added to the network, the transaction, including the signature, becomes immutable. The signature alteration is done such that if you run a mathematical check on it, it’s still validated by the network. However, when you run a hashing algorithm on it, it gives a different result.

Let’s take a look at an example:

Input:

Previous tx: p9k5ee39a430901c91a5917b9f2dc19d6d1a0e9cea205b009ca73dd04470b9a6

Index: 0

scriptSig: 304502206e21798a42fae0e854281abd38bacd1aeed3ee3738d9e1446618c4571d10

90db022100e2ac980643b0b82c0e88ffdfec6b64e3e6ba35e7ba5fdd7d5d6cc8d25c6b241501

Output:

Value: 2000000000

scriptPubKey: OP_DUP OP_HASH160 201371705fa9bd789a2fcd52d2c580b65d35549d

OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG

The input in this transaction imports 20 BTC from output #0 in transaction p9k5e… Then, the output sends 20 BTC to a Bitcoin address (expressed here in hexadecimal 2013… instead of the normal base58). When the recipient wants to spend this money, they will reference output #0 of this transaction in an input of their own transaction.

Some definitions:

• Previous tx — an identifier of the previous transaction to the address A

• Index — input number (here we have only one input number: 0)

• scriptSig — first part of the validation script (contains a transaction signature)

• Value — the number of bitcoins to send in units of satoshi (one bitcoin = 100 million satoshis) (20 bitcoins in the example above)

• scriptPubKey — second part of the validation script, which also contains the receiver address B.

To verify that the amount of the previous transaction can be spent, it needs to combine the scriptSig of a new transaction with the scriptPubKey of the previous transaction, in order to ensure the result is true and valid; scriptPubKey simply checks the equality of the public key and the validity of the signature (OP_CHECKSIG).

In a Bitcoin transaction, the txid (short for transaction ID, or transaction hash) is an sha256d hash of all the fields of the transaction data. The value of the txid depends upon scriptSig. During a mining node process transaction, the node can mutate scriptSig so that the signature will stay valid, and the transaction will have the same effect, but the txid will change. For example, one can add an OP_NOP operation (that does nothing). Or for some sophistication, one can add two operations: OP_DUP and OP_DROP (the first one is duplicating the signature on the stack, and the second one removes it again). The signature is still valid, but the txid changes.

Another example: If the signature value is “3,” we can change it to “03” or “3+7-7”. Mathematically, it’s still the transaction value with a valid signature, but there are different hash results, since hashing depends upon how you write the value, and not the value itself.

A mutable transaction id for an existing transaction can be problematic for a number of reasons. For example, if you want to build a Layer 2 solution on top of the Bitcoin network, you need to make sure no one can alter Layer 1, since Layer 2 relies upon it.

Modifying the txid can cause issues if you’re spending or accepting unconfirmed funds. Here’s how SegWit solves this problem:

With SegWit, all malleable information is separated from the transaction into separate “witness data.” When computing the txid, it won’t include this malleable information. In this case, the identifier will never be able to change, as the problems will be fixed.

Here’s a SegWit transaction output example:

Index 0

Details

Output

Address

35SegWitPieWKVHieXd97mnurNi8o6CM73

Value

1.00200000 BTC

PkScript

OP_HASH160

2928f43af18d2d60e8a843540d8086b305341339

OP_EQUAL

SigScript

0014a4b4ca48de0b3fffc15404a1acdc8dbaae226955

Witness

30450221008604ef8f6d8afa892dee0f31259b6ce02dd70c545cfcfed8148179971876c54a022076d771d6e91bed212783c9b06e0de600fab2d518fad6f15a2b191d7fbd262a3e01

039d25ab79f41f75ceaf882411fd41fa670a4c672c23ffaf0e361a969cde0692e8

We can see that there is witness information, and that the data includes all the malleable information. The SigScript has much less hash information compared to the previous example without the SegWit transaction. This also means that it reduces a Bitcoin transaction size, and improves transaction speeds by removing the witness data from the original portion and appending it as a separate structure at the end.

Here are some of the benefits of SegWit:

Node performance — Transaction size is reduced, so that the Bitcoin network is less congested as nodes can verify blocks (or transactions) more quickly.

Transaction malleability — As discussed above, with SegWit, the signature moves from the transaction data to a witness data block. The txid is immutable, and protects transaction data from being hacked.

Linear scaling of signature hashing operations — Reducing transaction size adds more transaction data for a certain transaction as part of a batch. SegWit separates transaction signatures out from transaction data so that each byte of a transaction needs to be hashed no more than twice.

Increased security for multi-signature transactions — SegWit provides two different scripts: one to a public key, and another that directs payments to a script hash. In combining these scripts, SegWit boosts security by enabling a multi-signature (multisig) transaction.

Building on top of Layer 1 — SegWit is great for the Bitcoin development of Layer 2 protocols, such as the Lightning Network. In addition, SegWit activation boosts development work on other features, such as MAST (which enables more complex Bitcoin smart contracts), Schnorr signatures (which enable a transaction capacity boost) and TumbleBit (an anonymous top-layer network).

Protects the Lightning Network — Lightning Network micropayment channels rely on double-signed transactions to lock the initial deposits. To start a Lightning Network payment, the funds from both parties are sent to one double-signed address. In order to prevent cheating, the transaction should be double-signed before any funds are actually sent to the double-signed address. Both parties need to be synced in order to collect the outputs of transactions from the main blockchain. This required transaction ID is immutable.

In theory, SegWit can double Bitcoin’s throughput or TPS). However, while improving the Bitcoin network’s throughput is critical, even a theoretical doubling still remains too low for mainstream use of Bitcoin as a payment system.

Block size

Another proposal to improve Bitcoin’s on-chain scalability suggests increasing the block size. The idea is superficially simple: increasing the block size from today’s 1 MB to, for example, 8 MB would increase transaction throughput eightfold. For example, Bitcoin Cash (BCH) blocks were initially 8MB, and currently a BCH block is set at 32 MB. Such a vertical scaling approach adds many more transactions within one block. However, increasing the block size means that the blockchain can be many times larger — and that requires better computing capacity in order to process large-sized blocks. At the same time, this would decrease the security of the network to some extent, due to the decrease in effective honest hash power.

This may also lead to a scenario in which a network is concentrated into a few rich hands and, thus, may ultimately compromise decentralization and security, the main tenets of the blockchain. In terms of security concerns, it’s a common belief that a blockchain network is more secure if more network nodes participate in transaction processing. With the wider distribution of altcoin chains, fewer nodes will operate on any given blockchain.

This may actually make the blockchain less secure, since a smaller altcoin network may be more vulnerable to network attacks. For example, let’s say that we have about 10,000 nodes on a larger network. It will require at least 5,001 nodes (51%) be compromised in order to launch an attack on the network. If we slice 10,000 nodes into 50 smaller chains, each chain comprises 200 nodes, so it only requires 101 nodes to take down any smaller chain, which is what we call a 1% attack problem.

Another issue is cross-chain integration: although there are some solutions for handling cross-blockchain integration, the overall complexity of integrating smaller chains and altcoins will increase drastically. SegWit2x, a proposed compromise to the block size debate back in 2017, suggested that SegWit be activated as a first step, and after that, the block size will be increased to 2 MB. However, this proposal was not accepted by the majority of nodes in the Bitcoin network.

Off-chain solutions

Similar to the rationales for an on-chain solution, the Bitcoin community is also actively looking for off-chain solutions, sometimes called Layer 2 solutions. In off-chain scaling, the solution is to build an extra layer on top of the Bitcoin blockchain that can process all kinds of transactions with two participants. These transactions can then be batched and sent as one transaction on the blockchain. One of these off-chain solutions is called the Lighting Network.

Lighting Network

In January 2016, a white paper entitled The Bitcoin Lightning Network: Scalable Off-Chain Instant Payments was submitted by Joseph Poon and Thaddeus Dryja. In it, the contours of the Lightning Network were described.

Lightning is a decentralized network that uses smart contract functionality within a blockchain to enable instant payments across a network of participants.

Lightning Network’s Layer 2 payment solution scales blockchains and enables trustless instant payments by keeping most transactions off-chain. It builds a network of so-called payment channels, in which two parties commit a transaction and pay each other only. The process is instant, and the transaction doesn’t need to be validated, relayed and stored by every node of the Bitcoin network, as it’s only between the two participants.

By moving payments off-chain, the cost of maintaining channels is reduced over the volume of payments in that channel, enabling micropayments and small-value transactions for which the on-chain transaction fees would otherwise be too expensive to justify. Furthermore, Lightning Network scales the off-chain transaction throughput with modern data processing and latency limits, so that payments can process with great speed.

Let’s take a look at how the Lightning Network works.

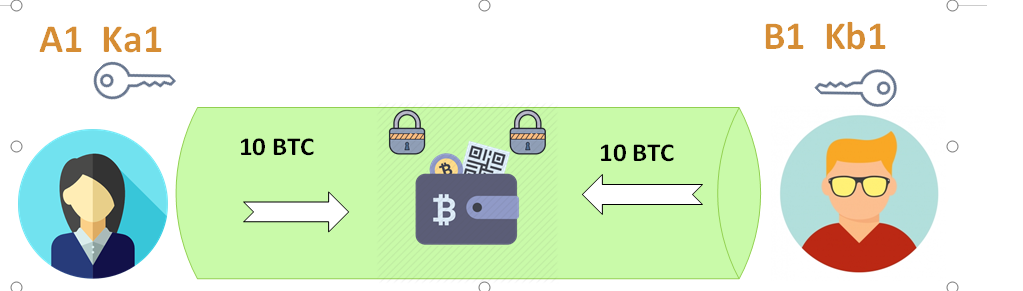

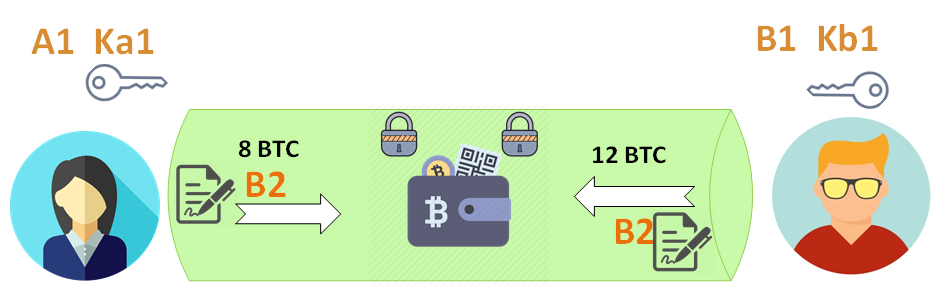

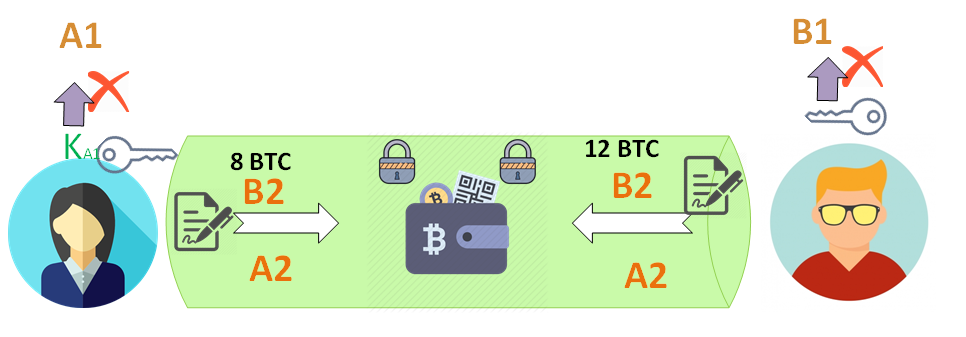

Example: Initially, Alice holds the A1 commitment transaction, and Bob holds the B1 commitment transaction. The revocation key for A1, K A1, is owned only by Alice, and the revocation key for B1, K B1, is owned only by Bob.

Suppose Alice and Bob each have 10 BTC in their account. Alice wants to send 2 BTC to Bob.

Alice and Bob both deposit equal amounts of money (in this case, 10 BTC) and each one puts a lock on it. This action of depositing equal amounts of money in a common box is recorded on the blockchain in the form of a “payment channel,” which is thereafter open between the two participants.

Alice creates a new transaction, B2, which allocates 8 BTC to Alice and 12 BTC to Bob.

Alice signs B2, and sends it to Bob.

Bob receives B2, signs it and keeps it.

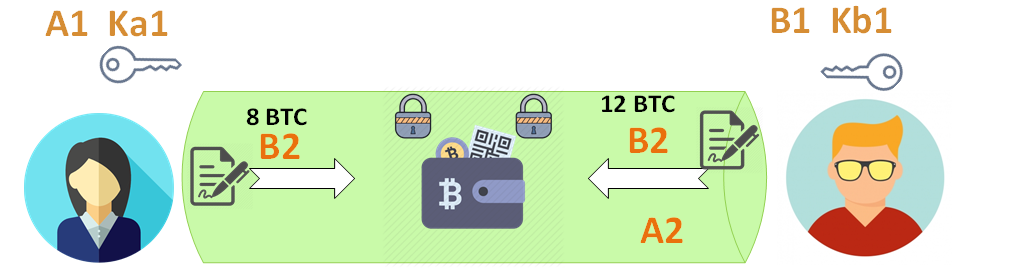

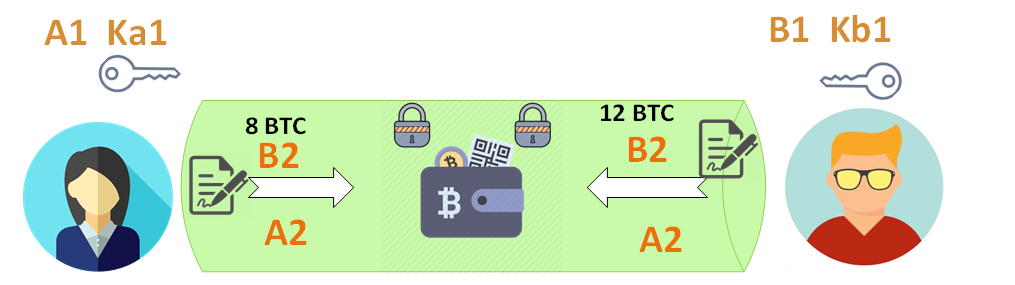

Bob creates a new transaction, A2, which allocates 8 BTC to Alice and 12 BTC to Bob.

Bob signs A2, and sends it to Alice.

Alice receives A2, signs it and keeps it.

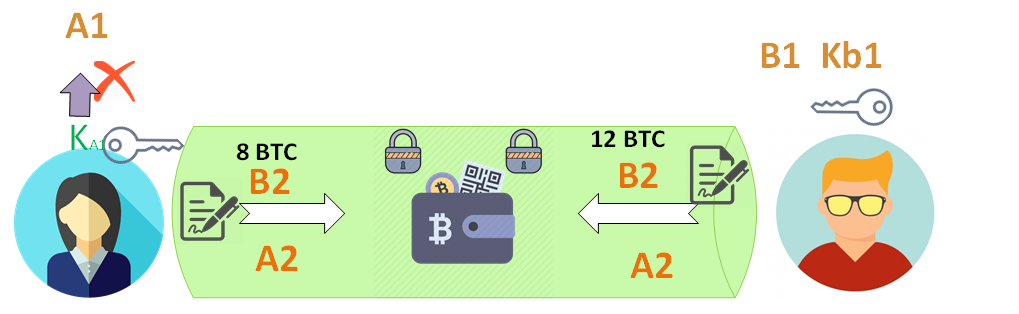

Alice provides Ka1, invalidating A1. She can then delete A1.

Bob provides K B1, invalidating B1. He can then delete B1.

To sum up, the payment channel is creating a combination of money pooling together for both parties, and then transferring the promise of ownership of the pooled-in money in the agreed-upon manner. When either Alice or Bob wants to close the channel, they can. “Closing a channel” simply means that both sides take their own money back. This opening of the box takes place on the blockchain, and the record of who owns how much from the box is recorded forever.

Lighting Network uses a Hashed TimeLock Contract (HTLC), a class of payments that uses hashlocks and timelocks to require that the receiver of a payment either acknowledges receiving the payment prior to a deadline by generating cryptographic proof of payment, or forfeit the ability to claim the payment, returning it to the payer. It allows transactions to be sent between parties who don’t have a direct channel by routing it through multiple hops (additional channels), so that anyone connected to the Lightning Network is part of a single, interconnected global financial system.

Let’s take a look at an example:

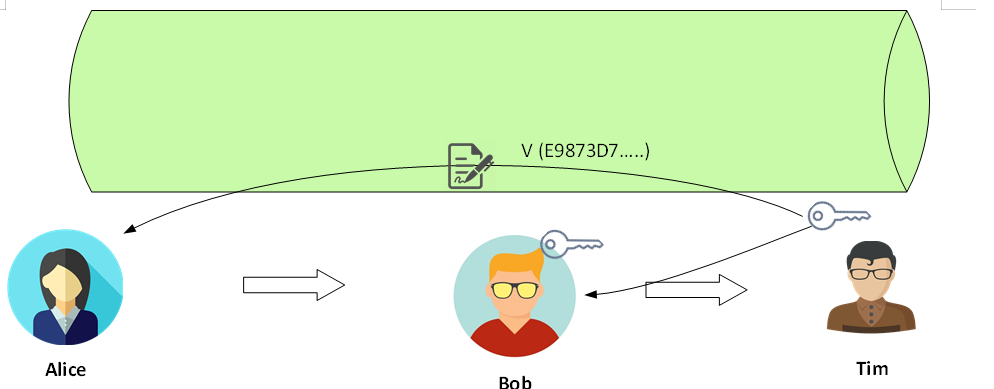

Alice wants to send a payment to Tim, but she doesn’t have a payment channel with Tim. Alice has a payment channel with Bob, who has a payment channel with Tim. The question is: How can Alice pay Tim?

To do so, Tim must create a cryptographic secret string (key), then hash it using a hash function (such as SHA-256) and send it to Alice. Tim also shares that hash with Bob. To simplify this written illustration, we’ll represent value as V.

HTLC

The Hash (V) is the lock, and the key is the code to unlock the HTLC.

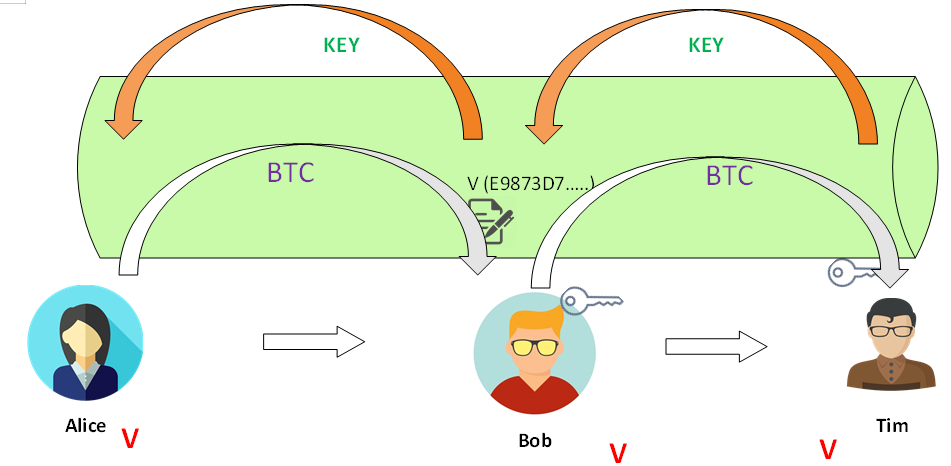

Alice creates an HTLC with Bob and tells Bob that she’ll pay him if he can produce the preimage of V within 3 days. Alice signs a transaction with a lock time of three days after its broadcast. Bob can redeem it, with knowledge of V, and afterward it’s redeemable only by Alice. The HTLC allows Alice to make a conditional promise to Bob, while ensuring that her funds won’t accidentally be burned if Bob doesn’t know what V is.

Bob does the same, creating an HTLC that will pay Tim if Tim can produce V within two days. However, Tim does, in fact, know V. Because Tim is able to pull the desired amount from Bob by using his key, Tim can consider the payment from Alice to be completed. Now, he has no problem sharing V with Bob so that he’s able to collect his funds as well.

Tim discloses the key to Bob within two days, and Tim gets paid by Bob.

Bob discloses the key to Alice within three days, and Bob gets paid by Alice.

After everyone cooperates, all of these transactions occur within Lightning Network. Everyone gets paid in a mechanical manner, as the Lightning Network is almost atomic in nature and bidirectional, meaning that either everyone gets paid — or nobody gets paid.

With Lighting Network, when a payment transaction is broadcasted, all the individual transactions are verified first, and they must match with the transaction history to avoid broadcasting false or incorrect transactions. There’s also a penalty that’s imposed on fraudulent transactions: if the Lighting Network detects a malicious actor in the system, they’re immediately charged with a penalty. This way, the entire network ensures credibility and consistency while discouraging bad behavior.

There are several benefits to using Lightning Network, as compared to on-chain transactions:

Quick and instant transactions: Settlement time for Lightning Network transactions is under one minute, and can occur in milliseconds.

Micropayments: Lightning Network allows micro-transactions in large amounts.

Transaction throughput: Fundamentally, there are no limits to the number of payments per second that can occur under the protocol. The number of transactions is only limited by the capacity and speed of each node.

Privacy: No blockchain records. The details of individual Lightning Network payment transactions aren’t directly and publicly recorded on the blockchain. Payments may be routed through many sequential channels, as each node operator will be able to see payments across their channels. However, they won’t be able to see the source or the destination of those funds if they’re non-adjacent.

Less congestion on-chain

Extremely low transaction fees: Transaction fees paid to intermediary nodes in the Lighting Network are frequently small, typically in millisatoshis.

Limitations

The Lightning Network is made up of bidirectional payment channels between two nodes which, when combined, create smart contracts. If at any time either party drops the channel, the channel will close and be settled on the blockchain.

Due to the nature of the Lightning Network’s dispute mechanism, it’s required that each participant always monitor their channel and track the state of the offline ledger being broadcasted to the network. The concept of a “watchtower” has been developed to solve this problem.

Conclusion

Bitcoin’s blockchain remains a groundbreaking decentralized payment system, but its inherent design prioritizes security and decentralization over scalability, resulting in limited transaction throughput compared to traditional payment networks. Innovations like SegWit and the Lightning Network represent critical advancements that enhance Bitcoin’s performance by increasing transaction capacity and enabling off-chain instant payments.

However, the blockchain scalability trilemma continues to challenge developers to balance scalability, security, and decentralization without compromise. As Bitcoin evolves, ongoing research and layered scaling solutions will be essential to support broader adoption and maintain the network’s integrity in an increasingly digital economy.

#LearnWithBybit